Format

Hardcover

Price

$26.99

Publication Date

April 08, 2025

ISBN

9781954641433

Page Count

264

Trim Size

6 X 9 inches

Printed In the United States

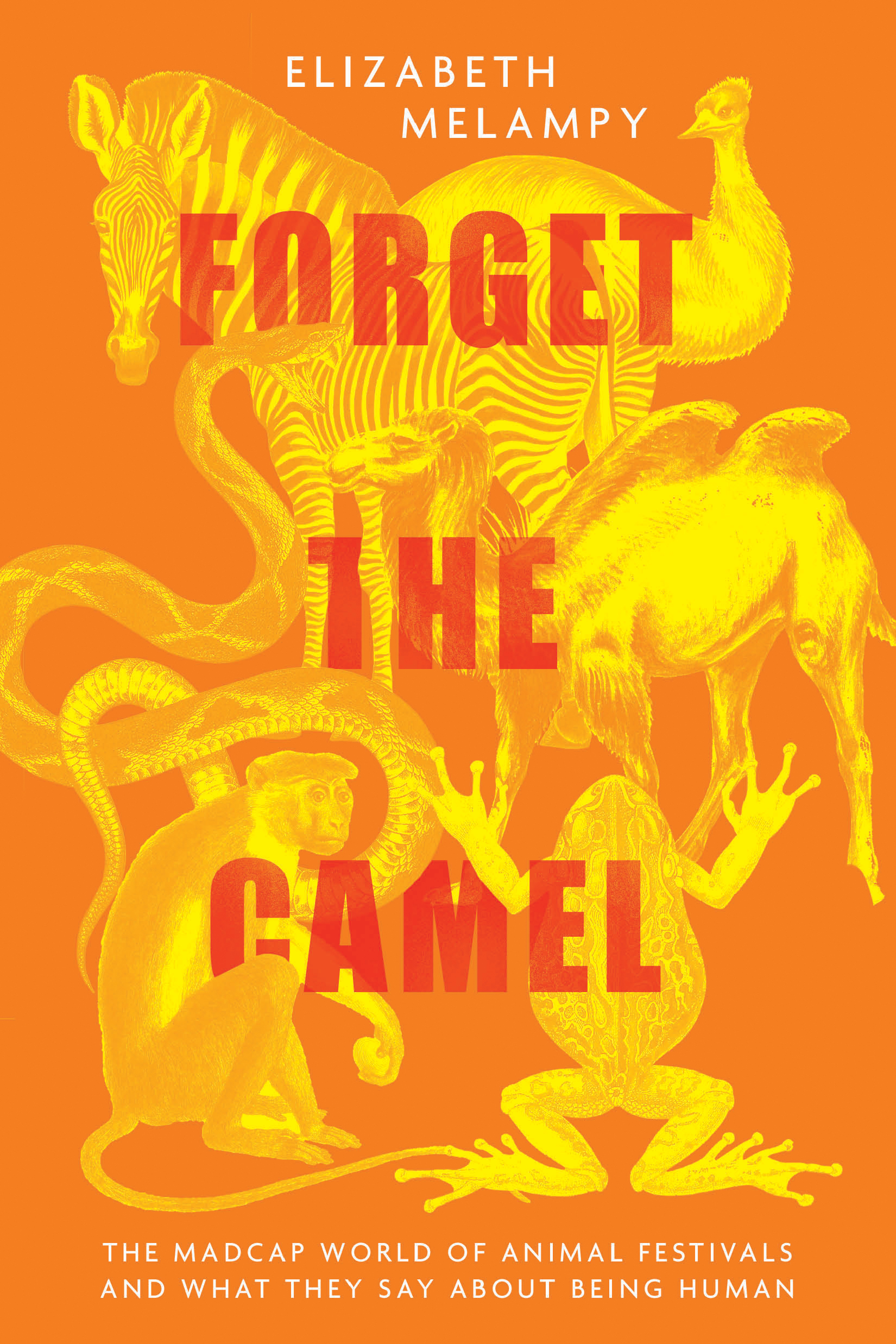

Forget the Camel

The Madcap World of Animal Festivals and What They Say about Being Human

by Elizabeth MeLampy

A raucous journey through eight animal festivals compels an environmental lawyer to ask what the stories we tell about animals reveal about our own humanity.

As the gates open at the racetrack in Virginia City, Nevada, three camels stumble out, ridden by amateur jockeys. A crowd of roaring spectators looks on gleefully, but as the camels approach the first turn, one loses its footing and crashes to the ground. While the camel’s handlers rush to the animal, the race’s emcee calls out in defense of the jockey, “Check on Charlie! Forget the camel!”

The International Camel and Ostrich Races is just one of hundreds of animal festivals that take place around the world every year, each putting animals on display for humans to gawk at, demonize, or adore. But why? What value do these festivals and their rituals hold, and why when the animals are in distress do we insist that the show still must go on?

In Forget the Camel, Elizabeth MeLampy meets the groundhogs, butterflies, rattlesnakes, lobsters, sled dogs, and other creatures we use to build community, instill fear, and transmit meaning. She shows how killing rattlesnakes in Texas represents a triumph over the Wild West; how lobster boils on Maine’s Atlantic coast show solidarity with the working class; and how the celebration each February of a single groundhog reminds us of our reliance on nature. In the process, she uncovers the symbolism we attach to animals and the stories we tell to rise above them.

Certain to be appreciated by fans of Yuval Noah Harari, Mary Roach, and Sy Montgomery, Forget the Camel is an immersive entry into the sights, smells, tastes, and noise of animal festivals across the country and a beautifully written step toward a compassionate future.

About the Author

Author Photo by Elizabeth Joy Sanders

Elizabeth MeLampy is a lawyer whose work focuses on animal rights and protection. A graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, she was named an Emerging Scholar Fellow by the Brooks Institute for Animal Rights Law and Policy in 2020 and received an award for her work with Harvard Law’s Animal Law & Policy Program in 2021. She clerked for judges in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and the Federal District Court in Arizona and litigated with the Natural Resources Defense Council. She currently lives in Boston, MA.

“From Groundhog Day and the Jumping Frog Jubilee to the ostrich races in Nevada and the Maine Lobster Festival, Forget the Camel offers a funny, poignant, and compelling tour of the roles of animal festivals in the American cultural landscape. Elizabeth MeLampy uses these often wacky events to pose important questions—why do we adore some species and detest others, what is the connection between humor and cruelty, and what makes humans special? This is the rare book that can make you laugh, cry, and change the way you think.” —Hal Herzog, author of Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals

“A fascinating and thought-provoking tour of animal-centered festivals around the United States. MeLampy thinks deeply and carefully about the animals she sees, revealing the gulf between our perceptions and the lived experiences of the creature at the center of our festivities. The result is a call for a different world, one where humans might see animals less as symbols, and more as organisms in their own right.” —Bethany Brookshire, author of Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains

“Elizabeth MeLampy’s Forget the Camel is a riveting, much-needed account of animal festivals from the animals’ point of view and what such festivals say about us and our relationships with nonhuman beings. Using the latest science, a host of stories, and some down home commonsense, she makes it amply clear that what unites communities, lifts spirits, and offers food, drink, and entertainment is anything but festive for the animals themselves. I can only hope that MeLampy’s detailed and compelling exposé of what goes on these human-centered events will force people to reassess what the animals feel and put an end to them once and for all. I learned a lot from reading this eye-opening book and I’m sure others also will.” —Marc Bekoff, Ph.D., author of The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy―and Why They Matter

“In the spirit of the anthropologist Margaret Mead, Elizabeth MeLampy gets up close and personal with her subject. In the process she exposes human behavior that I found to be at times disturbing, at others incomprehensible, and constantly revealing.” —Jonathan Balcombe, author of What a Fish Knows